Partager la publication "Mille Miglia 2015 Onboard 360° video same roads same car 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR n°722"

Ce weekend il y a eu les Mille Miglia, et voilà, il y a 60 ans personne n’a filmé Sir Stirling Moss & the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR – number 722 – et là en 2015, Sir Stirling Moss & the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR – number 722 – ont été réunis et ont participé au Mille Milgila 2015. Mercedes a réalisé une vidéo à 360° caméra embarqué à bord de la 300 SLR 722 !

1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR n°722 en 2015

Pourquoi 722 ? C’est le numéro que portait la Mercedes 300 SLR de Sir Stirling Moss qui a remporté la course mythique des Mille Miglia en 1955.

Le 1er mai 1955, Stirling Moss au volant de leur Mercedes 300 SLR n°722, et son navigateur Denis Jenkinson, tous deux viennent de rouler, au travers de l’Italie, durant 10 heures, 7 minutes et 48 secondes, à une vitesse moyenne de près de 160 km/h. Alors que la vitesse moyenne d’une automobile de l’époque ne dépassait pas 120 km/h, la 300 SLR pouvait atteindre 290 km/h. Par conséquent, en plus d’une superbe victoire ce résultat était considéré comme une véritable performance !

Pour commémorer cet évènement, l’un des plus célèbre et marquant de l’histoire de la course automobile, Mercedes a réalisé une vidéo à 360° ! Ainsi, Sir Stirling Moss vous emmène à bord de sa 300 SLR pour un grand tour des Mille Miglia 2015.

Mille Miglia – vidéo onboard 360°

La vidéo onboard 360 degrees est visible sur le site dédié :

http://tools.mercedes-benz.co.uk/current/360-degrees/mille-miglia.html

English summary

Mille Miglia – in 360 degrees

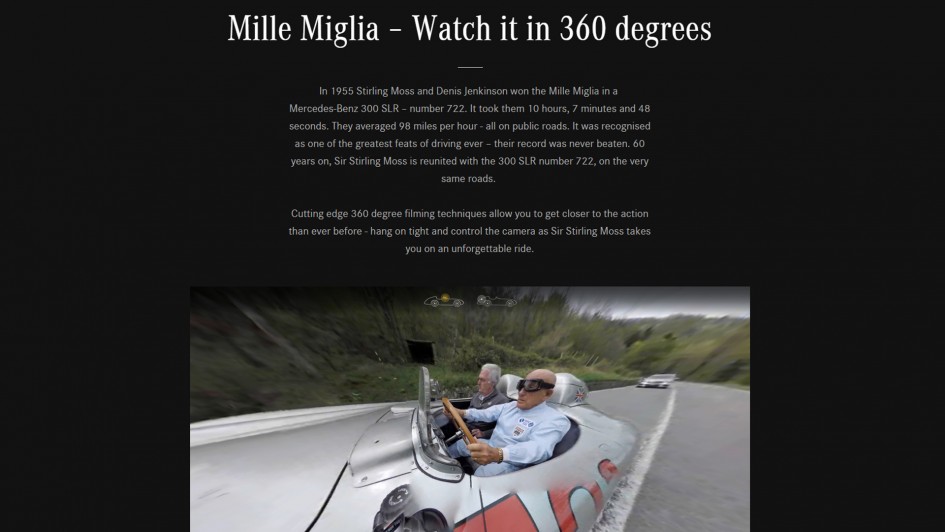

In 1955 Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson won the Mille Miglia in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR – number 722. It took them 10 hours, 7 minutes and 48 seconds. They averaged 98 miles per hour – all on public roads. It was recognised as one of the greatest feats of driving ever – their record was never beaten. 60 years on, Sir Stirling Moss is reunited with the 300 SLR number 722, on the very same roads.

Cutting edge 360 degree filming techniques allow you to get closer to the action than ever before – hang on tight and control the camera as Sir Stirling Moss takes you on an unforgettable ride.

The onboard video is here:

http://tools.mercedes-benz.co.uk/current/360-degrees/mille-miglia.html

Aux mains de Juan Manuel Fangio et de Stirling Moss, elle domina le championnat du monde des voitures de sport, remportant des victoires dans des épreuves aussi prestigieuses que la Targa Florio ou les Mille Miglia (co-pilote de Stirling Moss, le journaliste britannique Denis Jenkinson livra un récit épique de la victoire.

Histoire de moteur

The design of 300 SLR Mercedes-Benz

La Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR n’est pas dérivée de la Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (3 litres six-cylindres en ligne). Il s’agit en réalité de la version sport (donc biplace et carénée), de la fameuse Mercedes-Benz W196 (qui domina le championnat du monde de Formule 1 en 1954 et 1955) avec un moteur 8 cylindres en ligne.

Mercedes-Benz W196

La Mercedes-Benz W196 est la monoplace de Formule 1 avec laquelle Mercedes-Benz effectue son retour en Grand Prix après 15 ans d’absence, lors du championnat du monde de Formule 1 1954. Juan Manuel Fangio est champion du monde à son volant en 1954 et en 1955. C’est la dernière Formule 1 construite par Mercedes avant son retour à la compétition en 2010.

Perpétuant le mythe des Flèches d’Argent, la Mercedes-Benz W196 remporte son premier Grand Prix, à Reims avec Juan Manuel Fangio, dès sa première sortie en course et domine le championnat du monde jusqu’au retrait de la marque à l’issue de la saison 1955. En quatorze Grands Prix, la W196 décroche 10 succès (9 pour Fangio et 1 pour Stirling Moss) et permet à Fangio d’être sacré champion du monde à deux reprises.

Le moteur de la Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR

La 300 SLR reprenait notamment le moteur 8 cylindres en ligne, avec une cylindrée toutefois portée de 2 500 cm³ à 3 000 cm³. Ce moteur utilise une commande desmodromique* de fermeture des soupapes.

* Une commande desmodromique est un dispositif mécanique de commande – par exemple des soupapes – qui réalise la fermeture de celles-ci sans ressort de rappel. Le terme « desmodromique » est issu des deux mots grecs : « desmos » (« lien ») et « dromos » (« course »).

commande desmodromique

L’adjectif « desmodromique » s’applique de façon générale à des dispositifs mécaniques où la fonction de rappel utilise une commande active. Par exemple, beaucoup de motos possèdent une commande d’accélérateur sur laquelle un deuxième câble permet de couper activement les gaz au cas où le ressort de rappel des carburateurs lâcherait, ou si un grippage du câble d’accélération résistait davantage que la force du ressort de rappel. On parle alors de commande de gaz desmodromique.

Dans la réalisation d’un moteur automobile, les phases d’admission et d’échappement étaient les phases les plus complexes à traiter pour les ingénieurs. Diverses solutions ont été mises au point : soupapes à tiroir, soupapes automatiques à disques obturateurs, etc.. Ces systèmes présentaient tous le désavantage de ne pouvoir atteindre des régimes élevés. De ce fait ils furent rapidement abandonnés et ne sont plus aujourd’hui utilisés que sur des moteurs très lents (marine ou pompes mécaniques à essence) ou sur certains moteurs à deux temps (clapet).

Dans un moteur classique, utilisant les systèmes à ressorts et culbuteur, chaque soupape doit s’ouvrir et se fermer environ 25 fois et 50 fois par seconde (3 000-6 000 tours par minute); si le temps laissé pour que le ressort passe de sa phase de compression à sa phase de détente n’est plus suffisant c’est le sur-régime, et une possible casse moteur.

La commande desmodromique, permettant notamment d’atteindre des régimes supérieurs à 10 000 tr/min, fut alors imaginée par les ingénieurs. L’invention fut brevetée, le 1er avril 1893, par le parisien Claude Bonjour. La première tentative de commande desmodromique date de 1910. Elle fut installée sur le moteur d’une Arnott, un modèle anglais et utilisait le principe de la came à rainure.

Dès 1912, Peugeot s’intéressa au système et opta pour une came tournant dans un cadre. En 1914, Delage entreprit également la fabrication d’un moteur où levée et fermeture étaient assurées par une double came. En 1916, Isotta Fraschini s’engagea dans cette voie et développa des moteurs desmodromiques « mixtes » (le ressort existait toujours mais son mouvement était contraint par un asservissement mécanique). Ces moteurs étaient essentiellement destinés à l’aéronautique naissante.

La mise en place du système desmodromique, très complexe, mit un terme à son utilisation dans les années 1930. Il fallut attendre 1954 pour le voir réapparaître. La première firme à se lancer à nouveau dans l’aventure fut Mercedes-Benz qui équipa ses Formule 1 et son modèle 300 SLR de deux systèmes desmodromiques. Tous deux faisaient appel à une double came, mais l’un utilisait un basculeur à levier, l’autre un basculeur à pincette. Cette technique a été utilisée également par la firme O.S.C.A. appartenant aux frères Maserati sur la barquette 2000 Desmodrimico présentée en 1960.

The Engine legacy

The 300 SLR Mercedes-Benz

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR (W196S) was an iconic 2-seat sports racer that took sportscar racing by storm in 1955, winning that year’s World Sportscar Championship.

Mercedes-Benz W196

The Mercedes-Benz W196 was a Formula One racing car produced by Mercedes-Benz for the 1954 and 1955 F1 seasons. Successor to the W194, in the hands of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss it won 9 of 12 races entered and captured the only two world championships in which it competed. Firsts included the use of desmodromic valves and Daimler-Benz developed mechanical direct fuel injection adapted from the DB 601 high-performance V12 used on the Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighter.

Mercedes-Benz W196

The new 1954 Formula One rules allowed a choice of naturally aspirated engines – up to 2.5 litres or 0.75 litres supercharged. The expected target range for competitive engines was 250 to 300 bhp (190 to 220 kW).

Mercedes’ 1939 2-stage supercharged 1.5-litre 64.0×58.0 mm V8 (1,493 cc or 91.1 cu in) gave 278 bhp (207 kW) at 8,250 rpm with about 2.7 atm (270 kPa) pressure. Halving this would have only produced 139 bhp (104 kW).

Studies by Mercedes showed that 390 shp (290 kW) at 10,000 rpm could be achieved from 0.75 litres with a supercharger pressure of 4.4 atm (450 kPa), with 100 hp (75 kW) required to drive the supercharger. Fuel consumption of this 290 bhp (220 kW) net engine would have been 2.3 times higher than a naturally aspirated one developing the same power. Since 115 bhp/l (86 kW/l) at 9,000 rpm was being developed by naturally aspirated motorcycle racing engines, it was decided that a 2.5-litre engine was the correct choice. This was a significant change of philosophy, since all previous Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix engines since the 1920s had been supercharged. Mercedes’ solution was to adapt direct fuel injection Daimler-Benz engineers had refined on the DB 601 high-performance V12 used on the Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighter.

By its introduction at the 1954 French GP the 2,496.87 cc (152.368 cu in) (76.0×68.8 mm) desmodromic valves straight 8 delivered 257 bhp (192 kW). The W196 was the only F1 car with such advanced fuel technology, giving it a considerable advantage over the other carburetted engines. Variable length inlet tracts were experimented with and four wheel drive considered. An eventual 340 bhp (250 kW) at 10,000 rpm was targeted for the 2.5-litre F1 motor.

The design of 300 SLR Mercedes-Benz

Designated « SL-R » (for ,Sport Leicht-Rennen’, in english: ,Sport Light-Racing’, later condensed to « SLR »), the 3-liter thoroughbred was derived from the company’s Mercedes-Benz W196 Formula One racer. It shared most of its drivetrain and chassis, with the 196’s fuel-injected 2,496.87 cc straight 8 bored and stroked to 2,981.70 cc and boosted to 310 bhp (230 kW).

The W196s monoposto driving position was modified to standard two-abreast seating, headlights were added, and a few other changes made to adapt a strictly track competitor to a 24-hour road/track sports racer.

Two of the nine 300 SLR rolling chassis produced were converted into 300 SLR/300 SL hybrids. Effectively road legal racers, they had coupé styling, gull-wing doors, and a footprint midway between the two models.

When Mercedes canceled its racing program after the Le Mans disaster, the hybrid project was shelved. Company design chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut, architect of both the 300 SLR racer and the hybrids, appropriating one of the leftover mules as his personal driver. Capable of approaching 290 km/h (180 mph), the Uhlenhaut Coupé was far and away the fastest road car in the world in its day.

In spite of the « 300 SL » in its name and strong resemblance to both the streamlined 3-liter straight 6 1952 W194 Le Mans racer and the iconic 1954 300SL (W198) Gullwing road car the W194 spawned, the 1955 300 SLR was not derived from either. Instead, it was based on the wildly successful 2.5-liter straight 8 1954–1955 Mercedes-Benz W196 Formula One champion, with the W196’s engine enlarged to 3.0 liters for the sports car racing circuit and designated « SL-R » for ,Sport Leicht-Rennen’, in english: ‘Sport Light-Racing’, later condensed to « SLR ». All were the work of Mercedes’ prodigious design chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

The engine of 300 SLR Mercedes-Benz

The 300 SLR was front mid-engined, with its long longitudinally mounted engine placed just behind the front axles instead of over them to better balance front/rear weight distribution. A welded aluminum tube spaceframe chassis carried ultra-light Elektron magnesium-alloy bodywork (having a specific gravity of 1.8, less than a quarter of iron’s 7.8), which contributed substantially to keeping dry weight to a remarkably low 880 kg (1,940 lb).

The W196’s 2,496.87 cc (76.0 x 68.8 mm) straight-8 was bored and stroked to 2,981.70 cc (78.0 x 78.0 mm), boosting output from 290 bhp (220 kW) at 8,500 rpm to about 310 horsepower (230 kW) at 7,400 rpm, depending on intake manifold. Maximum torque was 318 N·m (235 lb·ft) at 5,950 rpm (193.9 psi (1,337 kPa) BMEP (The mean effective pressure is a quantity relating to the operation of a reciprocating engine and is a valuable measure of an engine’s capacity to do work that is independent of engine displacement. When quoted as an indicated mean effective pressure or IMEP (defined below), it may be thought of as the average pressure acting on a piston during a power stroke of its cycle)

Like the W196, the engine was canted to the right at 33-degrees to lower the car’s profile, resulting in slicker aerodynamics and a distinctive bulge on the passenger side of the hood shared with the streamlined Type Monza Formula one car. To reduce crank flexing, power takeoff was from the center of the engine via a gear rather than at the end of the crankshaft. Other notable features were desmodromic valves, and mechanical direct fuel injection derived from the DB 601 high-performance V12 used on the Messerschmitt Bf 109E fighter.

Fuel was a high-octane mixture of 65 percent low-lead gasoline and 35 percent benzene; in some races, alcohol was also used to further boost performance. As a rule, the car left the starting line with 44 gallons and more than nine of oil on board, although Moss and Jenkinson began their assault on the 1955 Mille Miglia with as much as 70 gallons of fuel.

To enhance stopping power extra wide diameter drum brakes too large to fit inside 16″ wheel rims were used, mounted inboard with short half shafts and two universal joints per wheel. Suspension was four-wheel independent. Torsion bars fitted inside the frame’s tubes were used in the double wishbone front. To prevent cornering forces from raising the car, as occurs with short swing axles, the rear used a low-roll center system featuring off-centered beams spanning from each hub to the opposite side of the chassis crossing one-another over the centerline. Nevertheless, snap-oversteer could be still a notable problem at speed.

Mercedes team driver Stirling Moss won the 1955 Mille Miglia in a 300 SLR, setting the event record at an average of 157.650 km/h (97.96 mph) over 1,600 km (990 mi). He was assisted by co-driver Denis Jenkinson, a British motor-racing journalist, who informed him with previously taken notes, ancestors to the pacenotes used in modern rallying. Teammate Juan Manuel Fangio was second in a sister car.

Bonus video via Petrolicious

Sir Stirling Moss and this Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR Remain Unbeaten

Few triumphs have inspired drivers like Sir Stirling Moss’ victory at the 1955 Mille Miglia. Then just 25 years old, driver Moss and co-driver Denis Jenkinson roared through 992 miles of Italian countryside in just 10 hours, 7 minutes and 48 seconds. Average speed? 98.53 miles per hour.

Here, Moss tells the story of his victory in his own words.

“Once the flag fell, I went flat out. Obviously, when I’d see a car I caught up with, I really felt great about it, but I had no idea of the enormity of what it meant to myself because it’s really—it’s quite the thing to have on your CV.’ - Sir Stirling Moss

Finishing ahead of the then-two times Grand Prix World Champion Juan Manuel Fangio, Moss’ achievement has long since been labeled “The greatest race”—a title that probably won’t be applied to any other motorsport event ever again. The 1955 Mille Miglia had it all: incredible drivers, now-iconic machines like the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR #722, and a harrowing course that was dangerous beyond belief.”

How dangerous? Moss said he had to wiggle the car from left to right on the road so that spectators would take a few steps back as he flew through the often small Italian towns along the route.

“Oh, I’m certain it’s my greatest win. I can’t think of any other car in the world that would have given me the opportunity to achieve the speeds we did.”- Sir Stirling Moss

Called SLR for Sport Leicht-Rennen (“Sport Light-Racing” in English) the 300 SLR was the world’s most advanced race car of its time: direct fuel-injected straight-8 engine, roughly 310 horsepower, and a top speed of around 180 mph (290 km/h).

“The 722 is a really strong car… The fact the car’s really old doesn’t matter—that car, the way it is now, I reckon we’d beat any other cars, anyway!”

- Sir Stirling Moss

Sir Stirling Moss and the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR #722 are Unbeatable via petrolicious.com

Source et images :

Mercedes-Benz

… et synthèse des pages Wikipedia :

Mercedes-Benz W196 FR

Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR FR

Mercedes-Benz Commande desmodromique FR

… and summary of Wikipedia pages:

Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR EN

Mercedes-Benz W196 EN

Partager la publication "Mille Miglia 2015 Onboard 360° video same roads same car 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR n°722"